In Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis the younger Scipio in a dream meets his famous grandfather, Scipio Africanus Major, and is carried up by him to the heavens; he looks down upon Carthage ‘from an exalted place, bright and shining, filled with stars’:

As I looked out from this spot, everything appeared splendid and wonderful. Some stars were visible which we never see from this region, and all were of a magnitude far greater than we had imagined…. And, indeed, the starry spheres easily surpassed the earth in size. From here the earth appeared so small that I was ashamed of our empire which is, so to speak, but a point on its surface. (trans. Stahl, 1952, p. 72)

His grandfather shows him the nine spheres which make up the universe— the celestial sphere, ‘embracing all the rest…confining and containing all the other spheres’, in which ‘are fixed the eternally revolving movements of the stars’, and beneath it, revolving in an opposite direction, those of the seven planets down to the moon (‘below the moon all is mortal and transitory, with the exception of the souls bestowed upon the human race by the benevolence of the gods. Above the moon all things are eternal’), and beneath it the earth, never moving. He is amazed by the great and pleasing sound of the music of the spheres:

That…is a concord of tones separated by unequal but nevertheless carefully proportioned intervals, caused by the rapid motion of the spheres themselves. The high and low tones blended together produce different harmonies…. Gifted men, imitating this harmony on stringed instruments and in singing, have gained for themselves a return to this region, as have those who have devoted their exceptional abilities to a search for divine truths. The ears of mortals are filled with this sound, but they are unable to hear it. (pp. 73–4)

This profoundly influential and highly poetic passage (which was admired by medieval readers and was echoed by some of the greatest medieval writers), besides being a fine statement of the dominant view of the cosmos, and of the nature of music, may suggest to the historian of medieval literature a number of other important patterns and ideas—as, for instance, a yearning (if not a rage) for order (note however that the ideal harmony is a balance of movement, not as is sometimes thought, a hierarchy that is fixed and rigid), as well as the sad realization of the gulf between eternal harmony and the life of man in this world.

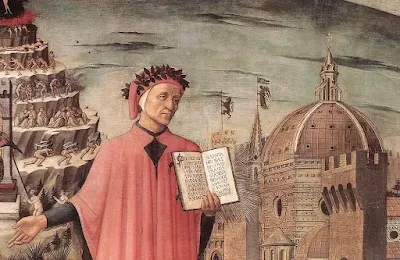

But an obvious point which should be made first is that this scene comes from a classical text, and it may justly be taken to highlight the importance of the legacy of the ancient world in medieval culture, and of the very remarkable continuities between the two cultures. The words ‘medieval’ and ‘the Middle Ages’ perpetuate an old and a misleading view which comes from Renaissance humanism and from the Enlightenment, that of a radical break with a lost and glorious classical past, followed at the end of the period by another radical break, the rediscovery of the ancient world and its culture, called, significantly, a ‘rebirth’ or a ‘renaissance’. Some sense of how oversimplified this view is can be seen in an episode early in the Inferno (c. 1307–21), where Dante, terrified by strange beasts, meets a shade, who identifies himself as the poet who ‘sang of that just son of Anchises who came from Troy after proud Ilium was burned’. Amazement turns to reverence—‘tu se’ lo mio maestro e ’l mio autore’, ‘thou art my master and my author’—and Virgil is to be his guide through hell. Later, Dante is introduced to another four great ‘authors’— Homer ‘the sovereign poet’, Horace the satirist and moralist, Ovid and Lucan.

These are venerated and, in varying degrees, used by medieval writers. The ‘authors’ form part of the school curriculum, with an introductory set of ‘minor authors’, including Donatus the grammarian, ‘Cato’ the moralist, and ‘Aesop’ the fabulist (in Latin), for beginners. Much was lost—a number of Roman authors and, since a knowledge of Greek became rare in the West, the first-hand experience of Greek literature. The story of the Iliad was known through an epitome, and Homer’s fame as a great poet survived, but since he was a Greek, his version was deemed to be a partial one by those who liked to think that their ancestors had been Trojans. Even more important were the historical effects of the chaos at the end of the empire, notably the ending of pagan culture and the disappearance of the old, educated pagan élite; what was often lost in consequence was an urbanity, learning lightly worn and elegantly expressed, a tolerance of differing points of view.

Because of the great changes in the cultural and social context, it is not surprising to find some strange transformations and misunderstandings of ancient stories and myths. What is important is that these stories and myths do live on, in hundreds of re-tellings, paraphrases or translations, made often into new and excellent works of art (so that in one English romance the story of Orpheus and Eurydice is transformed into a story of a rescue from fairyland, and the Greek and Trojan heroes in the so-called ‘romans d’antiquité’, although they worship ‘gods’, are in outward appearance, and in many of their inner problems, very similar to the chivalrous heroes of the twelfth century).

There are two points of significance here: first, that there is no question of a passive ‘acceptance’ of the ‘legacy’ of the ancient world, but rather an imaginative recasting or reinterpretation of the old stories, and second, that though some of the results of this may seem to a rigorously ‘classical’ viewpoint decidedly odd, it is evidence of an extraordinary closeness to and a familiarity with the stories of antiquity which implies a continuity with the past rather than any sort of ‘break’. The authors of the past were being used to serve the needs of the present. At the same time, there was throughout the Middle Ages a series of ‘classical revivals’ or renovationes, usually marked not only by a new enthusiasm but also by a desire to improve latinity and style—notably in the Carolingian period, in the twelfth century, as well as in the late medieval Italy of Petrarch and his successors. Humanitas is a quality that can be found in many medieval writers, ‘religious’ as well as ‘secular’; and one may distinguish various forms of ‘medieval humanism’.

In terms of the life of the intellect and of the spirit there is no doubt that the most revolutionary change was the triumph of Christianity. It endorsed that ancient view of the universe as the ordered and harmonious creation of God, and it offered its own vision of harmony in the vision of eternal life for the blessed. But it also made extreme demands, and sometimes brought extreme tensions as well as hope. Two conversions which had far-reaching effects may be taken as examples—those of an emperor and of a professor of rhetoric. In 312, before a battle, the emperor Constantine is said to have seen a vision of a cross of light, with the words ‘hoc signo vinces’: ‘by this sign you shall conquer’; he was ordered to place the sign on his helmet and on those of his men, which he did—and conquered. The great vision of the shining cross is one which impressed itself on medieval mystical piety. But its connection with victory and with war was no less influential. Although the ‘justness’ of a war had to be demonstrated, the way was opened for military campaigns in support of a militant faith, and for a great deal of bloodshed in the name of the Cross.

Another result was that a persecuted minority religion became an ‘official’ and a ‘state’ religion, which was to affect the lives of people both pious and negligent. It also developed a complex bureaucracy (which could be a ‘way to the top’ for talented young men of humble origins). And it became one of the strongest centres of power, even though the claims of the papacy were not always eagerly accepted by secular rulers or by political theorists. The conversion of Augustine in Milan in 386 was no less significant. He was only one among the number of the great ‘Fathers’ of the Church, but his influence was profound and pervasive—most obviously on theology, but not exclusively so. The Confessions (397–8), with its interest in the inner life of the soul and in the process of conversion and of self-knowledge, is echoed, whether strongly or faintly, in later works of spiritual instruction and of autobiography. His City of God (413–26), with its powerful images of the two opposing cities of Jerusalem and Babylon, and of the Christian man as an exile from his true home and as a pilgrim journeying through a hostile, deceitful and transitory world, is reflected in various kinds of medieval literature. The pilgrimage and the quest become dominant images, and the blend of faith and anxiety a characteristic one.

The one safe generalization that can be made about medieval Christianity is that it was complex and various. At one intellectual extreme, in the ‘schools’, one could find highly sophisticated philosophical arguments attempting to establish the tenets of the faith on rational and provable foundations; at another, much evidence of ignorance and indifference, or an intense popular piety that is often indistinguishable from magic. But this contrast was not simply one between the ‘clerks’ and the ‘lewed’ or the lay folk. There were ignorant and indifferent clerics, and lay men and women with a deep interest in theology and the life of the spirit. Nor was it a case of the ‘higher’ ecclesiastical strata simply handing down an official doctrine and spirituality to the people; the evidence suggests that the demands of popular piety were both intense and influential (in the establishment of the cults of saints, for instance). The parish clergy were often very close to their flocks in modes of life and of thought, and the parish church was a social as well as a religious focus.

There was a strongly ascetic element in medieval Christianity—most people at one point or another thought of (or were reminded of) the great gulf between the omnipotence of God and the littleness of man, of the inevitability of death which would bring an end to worldly pomp and pretensions, of the wiles of the devil and of the spiritual dangers of indulging the flesh. People were taught—though very many seem to have taken little heed of the doctrine— that the demands of the spiritual world were of more consequence than those of the temporal. It was the monastery above all which symbolized the ideal of a total commitment to the life of the spirit and the contempt of the world. Like all ideals in all periods of history, it was not always easy to maintain, but throughout the Middle Ages the monastery, as a centre of both spirituality and learning, made an important contribution to culture. Asceticism could be, and was, carried to extremes, but it is important to remember that alongside the contempt of the world expressing itself in a horror of sinful flesh, ‘the food of worms’, there is, in the mainstream of medieval Christianity, a firm belief in the dignity of man as the child of God.

There is also much change and development, both in doctrine (as in the changing views of Purgatory) and in spirituality (as is often pointed out, it becomes the ‘fashion’ in the high and later Middle Ages to stress the human and the pathetic aspects of the story of the Incarnation). Popular piety made urgent demands, and beside the traditional and institutionalized spiritual ‘vehicles’ of the Church, as symbolized by cathedral, parish church and monastery, new spiritual movements developed, sometimes persecuted, sometimes eventually accepted (as in the case of the Franciscans). These movements often begin with the urge to cure the corruptions and worldliness of the church by a return to the ideal of apostolic poverty. The medieval centuries saw the arrival of the friars (at first, significantly, often greeted with hostility by the monks, and by the parish clergy; later, accused of slipping into worldliness), and the establishment of béguinages and various kinds of lay communities.

There were many and various movements for reform; there was constant argument and criticism; the church faced challenges from without and from within. Medieval religion was far from being monolithic, or static; it was marked rather by vitality and by tension, with the church attempting to ‘harmonize’ these enthusiastic and sometimes potentially disruptive movements. There were tensions also in the spiritual life of individuals: preachers and teachers stirred the hope of eternal life in the heavenly Jerusalem (memorably expressed in some of the great hymns—‘O quanta qualia sunt ilia sabbata’), but also stirred anxiety about that great day of accounting at the end of time—‘Dies irae, dies illa…’.

It would be wrong to dwell so long on medieval Christianity that it might seem to be somehow separate from the rest of medieval culture. It was part of the whole texture of life. The sacred and the secular often seem to have overlapped completely, sometimes with astonishing results—in the fifteenth-century English Second Shepherds’ Play there is a comic scene with a stolen sheep which clearly and boldly parodies the sacred scene of the adoration of the Christ-child that follows. Perhaps more than any other practice, that of the pilgrimage illustrates the way in which the life of the world and the life of the spirit could collide or coalesce. Pilgrimage was the literal expression of that ancient idea of the Christian’s pilgrimage through life towards the heavenly Jerusalem; it was a solemn penitential act, a symbolic journey to death (a will had to be made, and one’s affairs put in order); it was also a spiritually efficacious practice drawing virtue and heavenly reward from the power of the shrine visited, whether at Jerusalem, Rome, Compostela, Walsingham, Canterbury (the shrine of the ‘holy blisful martyr’ Saint Thomas, who was reputed to help folk ‘whan that they were seke’), or at a host of others; it was also a way of seeing the world (as Chaucer remarks, when spring comes people start to long to go on pilgrimage) and in some of its aspects not altogether unlike modern tourist travel (one fifteenth-century German pilgrim rebukes the noblemen who carve their names and their coats of arms on the holy shrines; and Venetian galley-owners seem to have done very well from the pilgrim-trade to the Holy Land); it was also a way of meeting people and making new acquaintances. Moralists sometimes spoke severely about this, and about people like the Wife of Bath, who ‘koude muchel of wandrynge by the weye’, but the greatest poet of medieval England made a pilgrimage his central image of the jostling and often inharmonious world of different classes and human types, where, as might be expected, ‘diverse folk diversely they said’.

It would also be wrong to think only in terms of intellectual changes and movements. Medieval literature was the product of the new societies that emerged from the break-up of the late Roman empire, and continued to develop, as the predominantly rural, agricultural world of the early Middle Ages slowly and fitfully became the uneasy and relatively urbanized world of the fifteenth century. The patterns of rural life continued (in literature the voice of the peasant is rarely heard, unless he has been graced with a miracle or vision like Cædmon (fl. 670), and his way of life is rarely described), but towns grew in number and in size from the eleventh century, in a period of relative peace and renewal. To these crowded, noisy, and often violent and demanding centres people were attracted by the hope of wealth and the relative freedom offered by town life. Some became cities, and many developed considerable political power. The wealth of the great merchants and burgesses could be used for the building of civic churches and cathedrals and for the patronage of the arts. The towns were the cradle of the medieval universities (although the subsequent relationship between ‘town’ and ‘gown’ was often a violent one). Guilds and fraternities could provide education, welfare services, processions and pageants (and in the north, the great cycles of mystery plays). Towns were the setting for ceremonies in honour of patron saints and for fairs. They were centres to which travelling entertainers, minstrels and storytellers brought their wares. The considerable influence of the towns on literature does not always show itself in an obvious way—but it is obvious enough that Dante’s turbulent relationship with his native Florence is central to his inspiration, as are town life and mercantile values to Boccaccio’s Decameron (1349–51), while Chaucer is pre-eminently a London poet.

The castle, which is to most modern readers a more characteristic ‘image’ of the Middle Ages, is, if we think of a crusader castle or an English castle in Wales, a remarkable example of advanced military technology, but it could also be a symbol of oppression (a monk-chronicler of Peterborough records that in Stephen’s reign, evil and rapacious men ‘filled the land with castles’). It could also be the splendid setting for the social life of the aristocracy (often described in lively scenes in literature, as in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, c. 1375–1400). That idealization of the mores of the knightly classes, the large and very long-lived concept of ‘chivalry’, was played out on the battlefield but also in pageant and tournament, and was celebrated by writers, especially in the genre of ‘romance’ through heroes like Arthur, Gawain, Lancelot. In this fictional world youth and love reign. From the twelfth century, there develops an extensive vernacular literature of love in the lyrics of the troubadours and the trouvères, and in the immensely fashionable stories of Tristan and Iseult or Lancelot and Guinevere. In the formation and the dissemination of this, women (who, although their role in society was normally highly circumscribed, could sometimes wield considerable political power and, like the later Joan of Arc, change the course of history) seem to have played an important role, sometimes as authors (e.g. Marie de France, or the women troubadours), often as patrons, and always as a dominant and influential part of the audience.

In the early and high Middle Ages, the traditional bonds of society were a series of complex ties and obligations between a lord and his liegemen or vassals, loosely described as ‘feudalism’. The giving of service, aid and counsel was reciprocated by the granting of a gift, a beneficium (a fief, a grant of land; support and protection). This produced strains, conflicts of homage, aristocratic land-hunger and restlessness, as well as providing an apparent pattern for stability. But its influence is felt throughout medieval literature. In fiction at least, a lover might see himself as the vassal of his lady. And in both fiction and life, a Christian knight could see himself as the vassal of God, an idea which finds its finest expression in the hero’s death-scene in the Chanson de Roland (? c. 1100), where Roland, like a good liegeman, lifts up his glove to God as the angels bear his soul to Paradise. The immense stress on the necessity of personal loyalty meant that ‘breaking faith’ became almost the worst of sins, and the words for ‘traitor’ (as well as those for loyalty, faith or ‘troth’) became profoundly charged with emotion. It is significant that Dante, who is hardly a ‘feudal’ writer, reserves the deepest places in Hell for the great traitors—Ganelon (the betrayer of Roland) and Judas.

For most people, and for much of the time, life in the Middle Ages was far from being an ideal ‘mirror’ of the divine harmony. Invasions, wars, rebellions (like the Jacquerie in France in 1358, or the Peasants’ Revolt in England in 1381), and plagues (especially the terrible Black Death of 1348–9) all took their toll. Both the great and the humble could easily fall victim to violence. There were robbers and outlaws, who found refuge in the forests (in medieval literature typically the setting for magical events, and the haunts of madmen and fugitives from justice—and injustice). In sharp contrast to the orderly harmony of the heavens, the life of man in the unstable and transitory world below the moon seemed to moralists disorderly, sinful and without spiritual purpose. Langland begins his Piers Plowman (c. 1367–86) with a description of a ‘field full of folk’ all going about their business with little thought for God. In this vision of the world as it is rather than as it should be, society is full of corruption (memorably personified as Lady Meed). Many moralists, surveying the life around them, echoed the question, ‘How can one not be a satirist?’ Certainly, there was a rich and various tradition of satire, not all of it tending straightforwardly to the improvement of the world. And there were reformers, revolutionaries, and prophetic millenarian visionaries who proclaimed that the end of the world was foretold by the coming of an Antichrist or by the dawning of the third and final Age of the Spirit.

In order to maintain his faith in the immanent justice of God a medieval person must have needed all the fortitude extolled by the moralists and all the consolation offered by the church. But it would be misleading to exaggerate the ‘disharmony’ of medieval life. Most of Europe at various periods enjoyed times of peace and prosperity. Nor should one underestimate the capacity of human beings to endure and to carry on. And as in all traditional societies, a round of rituals and ceremonies and festivals—religious, agrarian, civic— maintained and ensured continuity. The desire for stability and order is reflected in the ‘mirrors for princes’, the books of instruction for rulers on how to govern a realm justly and in peace. Royal pageantry—coronations, marriages, progresses, solemn funerals—celebrated and by implication urged the stable continuity of the kingdom.

There were also intellectual patterns of harmony. The ideal merging of rest and action was to be found in heaven, but some mystics attempted to glimpse it on earth through contemplation. A characteristic emphasis on reason can be seen not only in the intricate and compendious Summae of the philosophers, but in the way Reason appears as a personified character in some philosophical poems. These patterns could also be found in the contemplation and study of the orderly universe. There was much discussion of the numerological mysteries, and of the numerological basis of music (Boethius distinguished musica mundana, the music of the universe, expressing the principle of concord through numerical ratios, musica humana, the harmony of the microcosm of man, the concord of body and soul, and the equilibrium of man’s ‘temperament’ (a word which still reflects these ancient views), and musica instrumentalis, the music made by man, which should imitate the harmony of the spheres and follow its laws of proportion). In his Parliament of Fowls (c. 1380), Chaucer shows Nature—the viceregent of God—maintaining the order and continuity of life in the diversity of species.

The Middle Ages saw considerable progress in many areas of scientific thought (thanks to the Arabs, much of Greek science had been rediscovered). And this interest in science was shared by creative writers. Here the most notable example is Chaucer, the most scientifically minded of the great English poets. He wrote A Treatise on the Astrolabe and possibly The Equatorie of the Planetis, and, although he self-deprecatingly remarks in his House of Fame (c. 1374–85) that he is too old to ‘learn of stars’, he seems to have had a knowledge of quite up-to-date astronomy. Dante, too, had scientific interests; and from our point of view, it is of interest that at the end of Paradiso, when he describes ‘la dolce sinfonia dell’altro Paradiso’, his vision of the wheel of the blessed is one of harmonious movement (‘but now my desire and will, like a wheel that spins with even motion, were revolved by the Love that moves the sun and the other stars’).

Medieval literature is the product of a ‘traditional’ society, one that prized the handing on of beliefs, mores and stories. ‘Old books’ is a term of approval— as against ‘novelty’. There is in fact much innovation and individuality, but it is often carefully disguised (the story, we will be told, really comes from an old book, or the experience occurred in a dream—as if our easy modern acceptance of the ‘truth’ of fiction did not come so easily then). The art of the medieval writer consisted largely in the playing of delicate variations (rather in the manner of a musical composer) on traditional forms, matter and formulas. It is important, too, to remember that the central ‘literary’ tradition, with its connections with classical antiquity, its ‘authors’ and its ‘books’ and its manuals of rhetoric, is far from being the only, or indeed the most important one. Although literacy seems to have increased during the course of the Middle Ages, it was never widespread, and ‘literacy’ in the narrower sense of an ability to read and write Latin was even more limited. But there was a very important non-literary culture. As in many traditional societies, beliefs and examples were handed on very often by word of mouth, by parents, nurses, older people. What is now called ‘oral literature’ was of great importance.

There are many references to the ‘singing’ or ‘telling’ or ‘hearing’ of stories; and it seems likely that there was a variety of ways of performing such works. Even the more ‘literary’ authors seem to have had a very close (and to a modern author, an enviably close) relationship with their audience. It is important not to think of ‘oral/popular’ and ‘literate/learned/courtly’ cultures as quite opposed and separate entities. There was constant interaction—a folk-tale or a motif from a popular story or song would be taken up and used and changed by a more literary writer; stories and forms from the ‘higher’ culture would find their way into the oral tradition. And literature, whether ‘written’ or ‘oral’, was only one of the ‘media’ by which instruction and entertainment came. There were the visual images of drama and pageantry. Pictures (used by the church in windows and wall-paintings as ‘laymen’s books’) were also important. The poet Villon (c. 1431–63) imagines his old mother saying: ‘I am a poor old woman who knows nothing and has never read a letter. In my parish church I see Paradise painted, where there are harps and lutes, and a Hell where the damned are boiled. The one frightens me, the other gladdens and rejoices me’ (Testament, 893–8).

Much of medieval literature has been lost, and much no doubt was never written down, but what has survived shows an extraordinary variety of forms and genres. Some are continuations or developments of those of the literature of antiquity; others (like some of the specifically Christian genres, such as the miracle play) have no connection with classical antiquity. And there is a similar linguistic variety. Medieval Latin was the language of the ‘clerks’, and used as a still living language; it produced a fine literature, by no means limited to works of doctrine and devotion, but including plays (secular as well as religious), sharp satires, and many very secular lyrics (like those in the famous twelfth-century Carmina Burana) as well as hymns and sacred songs. But even its greatest achievements were matched and often overshadowed by those of the vernacular literatures. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the courtly culture of France was dominant and influential: the fashionable romances (often with stories coming from Celtic sources—Geoffrey of Monmouth’s account of the history of the Britons, and especially of the rise and fall of the great king Arthur seems to have started something of a ‘Celtic revival’) spread to Italy, to Scandinavia, to Germany.

The development of English literature in this period has some distinctive features. It is a remarkable and a fortunate fact of history that a large and varied body of early writing in Old English or ‘Anglo-Saxon’ has survived— including some impressive poetry written in a form of alliterative verse. This literary tradition was not an entirely isolated one: there was a thriving tradition of ‘Anglo-Latin’ writing with which it had connections, as it did with the ‘central’ (and predominantly religious) European Latin tradition. However, with the Norman Conquest of 1066, English was no longer the language of the new upper classes, whose literature was in French—and in the characteristic local variety that developed, Anglo-Norman (the literature in Anglo-Norman is diverse and by no means ‘provincial’: it produces, for instance, one of the great Tristan romances). Writings in Latin continue throughout the period. The scattered remains of English writing from the late twelfth century on are usually humble, and in a language which, not surprisingly, has undergone some deep changes. But in the fourteenth century, the status of English improves (and gradually Anglo-Norman fades away), and from the second half of this century we have a dazzling array of works—Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, Piers Plowman, and other poems written in a form of the old alliterative metre; the writings of Chaucer and Gower show an easy elegance and a familiarity with French and Latin literature, and in the case of Chaucer, England’s first vernacular poet of European stature, a remarkable knowledge of Italian. Two results of this curious cultural history deserve mention: there is, firstly, compared with continental literatures, often a kind of ‘time-lag’— prose romances, for instance, which appear in French in the thirteenth century, are not found in English until the fifteenth. On the other hand, literature of a ‘popular’ kind is well represented in the surviving remains.

No one can fix a date on which the ‘Middle Ages’ ended and the ‘Renaissance’ began. The best that can be done is to isolate some changes and developments (many of which certainly have ‘medieval’ roots) which gradually spread alongside older traditional patterns. These changes are economic and social, and intellectual. The invention and spread of printing in the second half of the fifteenth century, for instance, eventually produced something of a cultural ‘revolution’, but it is easy to exaggerate both its effects and the speed at which it occurred (in Northern Europe for a long time, printed books looked like, and were usually treated as if they were, manuscript books; and the tastes of both printers and readers seems to have been generally conservative). It is possible to argue that much of the impetus for the Reformation came from within late medieval religion itself. And alongside the older kinds of ‘medieval humanism’ there developed the so-called ‘New Learning’, the last and the most influential of the medieval renovationes of classical antiquity. The intense devotion to the authors of antiquity that pervades the life of Chaucer’s older contemporary Petrarch, who played such an influential role in this, takes us back to our starting-point. His imitation of Virgil, the Africa (conceived in 1333, abandoned in the 1350s), celebrates Scipio and the history of the struggle between Rome and Carthage (‘my Cicero’ was one of his favourite authors, and Scipio, whom he takes to exemplify both Roman and Christian virtues, one of his heroes). It is incomplete, and in one way is a lament for the glories of the past. Petrarch’s view of the present and of the future also tended to be a melancholy one, but in his successors the idea of the break with the classical past became a real and a rigid one.

But there are continuities at the end of the period as well as at its beginning. If the schoolchildren of the Renaissance were brought up on ‘chaste’ Latin, and if they were instilled with religious views that were in dogmatic content either different from those of earlier times, or stricter, much about their world view remained very similar. The old scientific view of the cosmos that we saw in the Somnium Scipionis lived on for a very long time. Men who were prepared to kill each other for the sake of doctrine often expressed their personal devotion in very similar ways, which are the direct or the indirect descendants of the emphases and the practices of medieval ‘affective’ piety (examples may be found in The Book of Common Prayer, or in the Lutheran chorales so movingly set by Bach). And there are continuities in literature, both sophisticated (as in The Faerie Queene) and popular (as in the ballads). Antiquarian and historical interest in the period and its culture continued and was joined in the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries by a Romantic rediscovery of the middle Ages, which produced some fine as well as some extraordinary works of art.

These two strands have continued to interweave in our more modern attempts to understand the literature of the medieval past. The first good ‘edition’ of the text of The Canterbury Tales by Tyrwhitt in 1775 was a premonition of a long series. Much more has been discovered about the elusive ‘context’ of medieval literature—about the history and development of the vernacular languages and their varieties, for instance. Here the historical research of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has made vital contributions: in our understanding of philosophical concepts and modes of argument, of ideological concepts such as ‘chivalry’, of the structures of medieval society (as in the work of Marc Bloch, 1961, and others); literary students have been able to draw on the work of historians of art to illuminate images and iconographic patterns in their texts, on the work of historians of music—and on the twentieth-century movement to restore ‘authentic’ performances and instruments—and on the work of anthropologists in understanding ‘traditional society’ and oral literature.

Some medieval authors early established a ‘canonical’ position—notably, Dante in Italy, and in England Chaucer, who is acclaimed as a leading poet from the early fifteenth century (and who provokes the first distinguished criticism of an English medieval author, in Dryden’s splendid seventeenth-century appreciation). Other writers and works slip out of sight, and are rediscovered by enthusiastic later critics. Thomas Warton’s History of English Poetry (1774–81) treats a wide range of the earlier literature: it is remarkable for the breadth of its knowledge and for the sympathy of its judgements. From the end of the nineteenth century, medieval literature became a subject for academic university criticism, and the products of this in general reflect the changing emphases and fashions of that discipline. However, the particular characteristics of the literature have meant that the criticism has usually been more attentive to the historical contexts, and more wholeheartedly comparativist in scope (as in the work of W.P.Ker, 1897) than that of later periods has been.

Distinctive too has been a tension (often a creative one) between a ‘Romantic’ enthusiasm for early literature, leading, for instance, to a stress on the quality of individuality, and a firmly non-romantic approach, which would stress the importance of tradition and convention (seen, for instance, in the work of E.R.Curtius, 1953, on rhetorical topics). More recently, structuralist, post-structuralist, feminist and neo-historicist studies have appeared. Rather interestingly, medieval literary works have always presented some of the problems that these later theories have had to address: the frequent absence of the ‘author’, the instability of the ‘text’, the fragmentary context, the sense of difference or ‘alterity’ alongside the flash of recognition, and so on. In the end, however, it is the quality of the best medieval literature that is its true memorial—as Edwin Muir in his Autobiography says of his discovery of medieval art in Italy: ‘things truly made preserve themselves through time in the first freshness of their nature.’

Source: Encyclopedia Of Literature And Criticism